Disability voices need to guide progress to a more inclusive Australia

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability has sat for its 31st and final public hearing of 2022, concluding the year with discussions on a Vision for an inclusive Australia.

Held in Brisbane, the public hearing tackled a range of issues and perspectives to assist with understanding how to create a more inclusive society for people with disability.

Universal design, human rights concerns, ableism and representation were all covered at the last week of hearings as witnesses from across Australia shared their experiences.

Autism visibility vital for Heartbreak High star

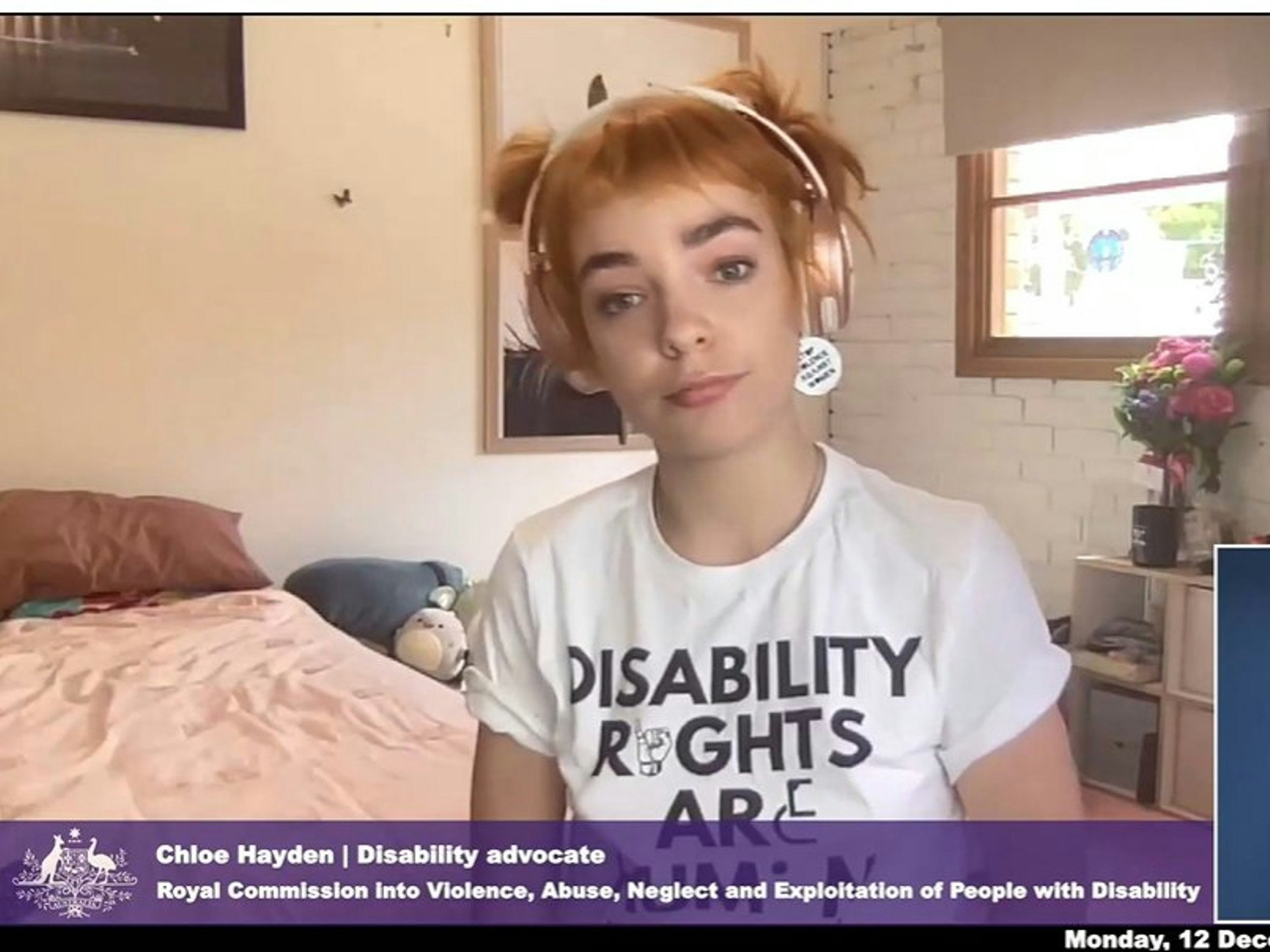

The Royal Commission featured two of Australia’s most recognised disability advocates, Australian of the Year and former wheelchair tennis champion, Dylan Alcott AO, and award-winning actress, Chloé Hayden.

Ms Hayden, 25, diagnosed with autism at the age of 13, stars in Netflix’s Heartbreak High, portraying Quinni, a character with autism.

Ms Hayden told the Commission that she initially felt scared by her diagnosis as it was viewed as a mental deficit because “something [was] wrong with your mind if you were autistic” and there was no positive representation for her in the community or mainstream media.

But by finding her own inclusive support network online, she says she finally realised there was nothing wrong with her autism diagnosis.

“When I couldn’t find any articles or anyone, period, talking about autism in a positive light, I made a blog post and it was a young girl screaming to the universe, begging to find just one more person like her,” says Ms Hayden.

“People started reaching [out] back to me, and I had hundreds, thousands of people who felt the same way I did, who also thought that they were aliens on this planet that was so far away from home.

“When I started to find the beauty in other people and when I started to find communities and when I knew that I was supposed to exist because there were hundreds of thousands of people just like me, that’s when I was able to start seeing the beauty in it myself as well.

“Now, as a 25-year-old, being autistic is something I am immensely proud of. It is who I am wholeheartedly and in its entirety.”

When asked about building a more inclusive Australia for people with disability, Ms Hayden highlights the ongoing importance of representation in social media and mainstream media.

As one of the few actors with autism to actually portray an autistic character, Ms Hayden says non-disabled actors represent autism in a way that is too stereotyped, such as Raymond in Rain Man or Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory.

Her hope is that mainstream media and society as a whole can listen, unlearn and relearn from disabled people to create more inclusive communities.

“It would be so wonderful to get to a point in our society where representation isn’t even a word that we need anymore because it is simply the norm,” says Ms Hayden.

“The media already has immensely impacted society’s view on disability.

“The same way that I grew up thinking that I wasn’t supposed to exist because I never saw representation of myself, we can change the media to make sure that young people grow up seeing themselves represented and knowing that they are supposed to exist.”

Alcott reinforces push for workplace inclusion

Mr Alcott, who is paraplegic, focused on a different aspect of inclusion to Ms Hayden’s – he spoke of workplace accessibility and inclusion.

He says that many employers continue to exclude disabled people as potential employees or consumers, and those that do provide an accessible space are not always inclusive.

“You can have the most accessible workplace ever, ramps, screen readers, a sensory room for people who are neurodiverse,” says Mr Alcott.

“Yet, if that person goes out to their desk and no one talks to them or doesn’t give them a promotion or sidelines them because of their unconscious bias about their disability, what’s the point of having the accessibility features?

“Accessibility and inclusion go hand in hand.”

Mr Alcott, who has spent much of 2022 pushing for disability inclusion and employment opportunities, says employers have to stop putting the onus on people with disability to speak up about their needs.

He wants society to work together with people with disability to create inclusive spaces.

“A person with an invisible disability has absolutely no pressure to tell anybody anything about themselves,” says Mr Alcott.

“It’s up to society and workplaces to do the work, to create inclusive cultures so people with invisible disabilities, all disabilities, can be their authentic self when they go to work.

“It often always falls on the people with disability to [explain] what [they] need.

“I say, no, you make yourself accessible and inclusive by educating yourself, investing in it so you’ve got a better understanding so then people with disability can then get [to work] and be the people that they want to be authentically at work every day and contribute.”

Attitudes impact human rights

Growing up with a brother with disability, Angel Dixon told the Commission she witnessed limiting and harmful attitudes that created serious segregation and feelings of shame in her family.

Yet when she suffered a stroke that impacted her mobility, she found her own standing in her family was suddenly lost.

“The challenging thing for me then was that not only was I an outsider in a society that no longer welcomed or understood me, but I was also an outsider in my own family,” says Ms Dixon.

“Human rights and attitudes are unequivocally tied, and the data and attitudes towards disability in Australia to me isn’t surprising, but it’s still pretty horrible.”

Negative attitudes towards disability remain evident in the healthcare and education systems, and Ms Dixon believes co-designed supports must be introduced to remove rigid perceptions of disability.

“The only way that we can fix all of these things that we’ve spoken about is by targeting all levels and focusing on co-design and not consultation, which means engaging people with disability at every phase in system and policy design,” explains Ms Dixon, “As well as utilising universal and inclusive design and transforming and transitioning out of non-segregated models.

“And I think it’s going to take a lot of time, effort and money, from an organisational and policy and Government level.”

Ms Dixon also says there needs to be a greater focus on language that supports people with disability, whether it is identity-first, person-first or their own identifier.

“As a community, we’ve actually moved towards disability status as our demographic identifier to steer away from ability and other euphemisms with unintentional ableist connections,” explains Ms Dixon.

“The way that people with disability represent themselves using language isn’t static, and people identify differently in general, but they also identify differently as they learn and change and grow as a person.

Ms Dixons says there should be structural support through the Government and organisations to promote the use of human rights and The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) inclusive language in society.

Penalties needed to create inclusive environments

Australia’s vision for an inclusive society has to include more consultation with people with disability when creating services or building physical spaces, says Centre for Inclusive Design (CfID) Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Dr Manisha Amin.

Dr Amin says both State and Federal Governments, plus all organisations, need to better understand how to support people with disability to meet their accessibility needs.

They should lead by example to prioritise accessibility and inclusion by creating universal designs that can cater for everyone.

“Currently, systems, environments, products, and services are predominantly designed by and for the people who make up the ‘majority’… this approach to design fails to consider those who identify as living with disability,” says Dr Amin.

“The people who have the best insights to design a better society for the future for everyone are people who have been impacted and excluded the most in the present society.

“Knowing the experience of a person with disability is the only way to plan and design for a person with disability, especially when we consider new technology.”

Dr Amins believes there should be harsher penalties in place to ensure organisations maintain a high standard of inclusive designs, policies and services.

If there are negative outcomes, she wants the appropriate mechanisms in place to rectify them.

For example, if a building has been designed with hearing loops to benefit hearing-impaired individuals, and yet the instructions for use are not visible, are there systems in place to improve the service?

“To encourage and maintain high standards of accessibility, serious penalties for not meeting the regulatory requirements need to be implemented,” says Dr Amin.

“At present, the laws and regulations penalising organisations and individuals in Australia regarding accessibility are not strong enough to discourage bad practice.

“The fines and penalties should be viewed as an incentive to do better.”

Dr Amin also says that anyone concerned with the upfront costs of building an inclusive space should understand that it is a cheaper expense in the long run when compared to retrofitting accessible features later.

Vision for an inclusive Australia was the final hearing for the Disability Royal Commission in 2022. It will return next year with the Final Report set to be delivered to the Governor-General by 29 September 2023.

For ongoing coverage of the Disability Royal Commission in the new year, subscribe to our Talking Disability newsletter.